Published first in La Prensa 17 December 2018

Hace millones de años, donde se encuentra ubicada la angosta franja de tierra que hoy en día llamamos Panamá, había un océano profundo. Cuando se formó el istmo, se desencadenó una cascada de eventos globales. Mirando hacia el futuro, el istmo podría volver a jugar un papel importante en el cambio global.

Cuando esta historia empezó, los continentes de América del Sur y del Norte, África, Asia, Australia, y la Antártida, formaban un solo “supercontinente”, llamado Pangea.

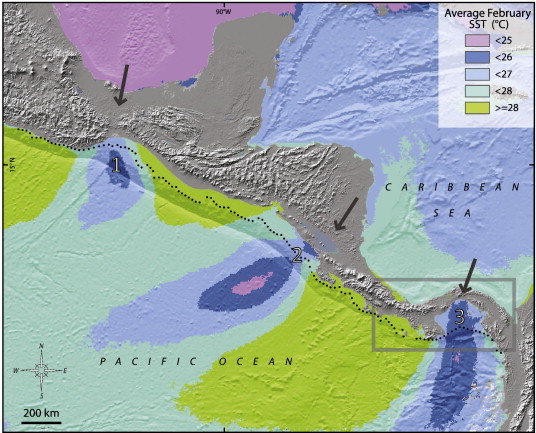

Hace aproximadamente 150 millones de años, Pangea comenzó a fragmentarse, formándose el Océano Atlántico. A la vez, una pequeña vía marítima se abrió, conectando el joven y angosto Océano Atlántico con el enorme Océano Pacífico. Esta vía se encontraba justo donde está Panamá actualmente y fluyó entre el Pacífico y el Atlántico durante los siguientes 125 millones de años, permitiendo el libre movimiento de animales marinos.

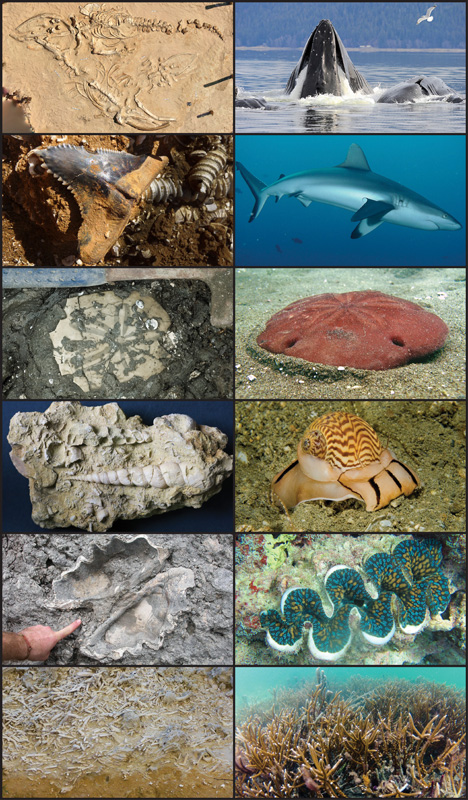

Más recientemente, hace solo 25 millones de años, una franja de volcanes submarinos en el océano Pacífico chocó con América del Sur a la altura de Panamá. Los volcanes más altos emergieron como islas, transformando la vía marítima en varios estrechos de menos profundidad. Los fósiles de Panamá muestran que estas islas volcánicas estaban cubiertas de exuberante vegetación y rodeadas de arrecifes de coral llenos de peces.

Poco a poco, las rocas del fondo del mar comenzaron a subir hacia la superficie, convirtiéndose lentamente en un puente terrestre que volvió a conectar América del Sur y del Norte. Este evento monumental tomó más de 20 millones de años.

¿Cuándo fluyó la última gota de agua salada entre los dos océanos? Los científicos están de acuerdo en que el puente terrestre completamente formado surgió hace apenas 3 millones de años, casi ayer desde la perspectiva de un geólogo.

Impacto

¿Por qué el mar es azul en el Caribe, pero turbio y a veces frío en el Pacífico? ¿Por qué no hay playas de arena blanca a lo largo del Pacífico? ¿Por qué hoy día el Caribe es tan diferente del Pacífico? Estas diferencias enormes entre los océanos se deben a la presencia del istmo.

Los impactos de la formación del istmo también se sintieron mucho más allá de Panamá. Las corrientes oceánicas se desviaron, muchos animales se extinguieron, y hubo repercusiones en el clima y la biodiversidad del planeta entero.

El puente creado por el istmo facilitó el movimiento de plantas y animales entre los dos continentes americanos. Las llamas y alpacas, icónicas de los Andes, son descendientes de camellos que migraron desde el norte hacia Sudamérica por medio del istmo.

Y la migración continúa hasta nuestros días: el coyote se dirige hacia el sur, mientras que el capibara se mueve hacia el norte.

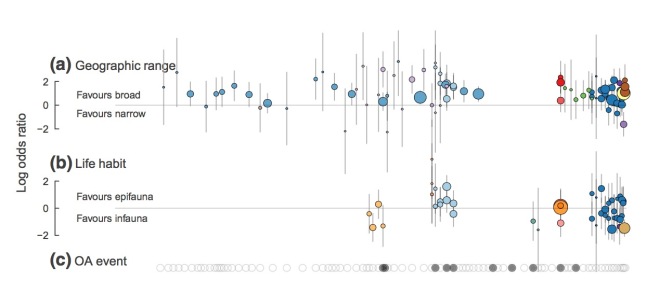

El nuevo puente también formó una barrera: los animales marinos ya no podían moverse entre los océanos. Sus poblaciones se dividieron en dos. Científicos de todo el mundo usan este evento como el momento “cero” en un reloj para medir cuánto tiempo tardó para que evolucionen nuevas especies.

La historia de esta pequeña franja de tierra que cambió el mundo coloca nuestra propia existencia en el planeta en un contexto de humildad.

Pero, ¿hacia dónde vamos en el futuro? Los geólogos predicen que eventualmente el Istmo de Panamá va a separarse y flotar hacia el Caribe. Otro océano profundo pudiera conectar el Pacífico con el Atlántico nuevamente. Pero no se preocupen, esto no sucederá antes de unos 20 millones de años.

Sin embargo, hay algo de lo que sí deberíamos estar muy preocupados. El aumento de las emisiones de dióxido de carbono (CO2) a través de la quema de combustibles fósiles para el transporte y la producción de energía, la agricultura industrial y la pérdida de los bosques está alterando el curso de la historia de nuestro planeta.

Mientras que los océanos y la atmósfera se están calentando, los glaciares (algunos de los cuales tienen un espesor de más de 5 km) se están derritiendo, haciendo subir los niveles del mar debido al ingreso de agua dulce del deshielo. A medida que el mar se calienta, también se expande, elevando aún más su nivel.

Desde la revolución industrial, el nivel del mar ha aumentado alrededor de 26 cm y las predicciones sugieren otro metro por encima de eso en el próximo siglo. Curiosamente, no todas las partes del océano se están subiendo por igual. De hecho, el lado caribeño de Panamá está acelerándose más rápido que el promedio mundial. Los científicos todavía están tratando de entender por qué esto es así, pero es un hecho innegable.

Y es un hecho desalentador para lugares como la ciudad de Colón. Colón se construyó cerca del nivel del mar hace más de 150 años para satisfacer la demanda de la “fiebre del oro” en California. Las inundaciones recientes se deben principalmente a un sistema de drenaje envejecido y mal mantenido: el agua no puede salir lo suficientemente rápido al mar. Con un metro adicional de nivel del mar significa que no solo muchas partes de la ciudad estarán bajo agua marina, sino que los afortunados que se encuentren en terrenos ligeramente más altos también serán más difíciles de drenar.

Es una verdadera receta para el desastre, para la ciudad que una vez fue resplandeciente.

Cuando se construyó Colón, nadie podría haber predicho el aumento del nivel del mar. Ahora es diferente. Con una gran cantidad de datos científicos podemos predecir y podemos actuar.

Al oeste de Colón nos encontramos el archipiélago de Bocas del Toro. En 1991 Bocas fue golpeado por un tsunami que llevó agua marina a 200 m dentro de las calles del pueblo. Si volviera a ocurrir un tsunami similar, el hecho de que el nivel del mar sea más alto ahora de lo que era hace 27 años significa que sería más destructivo y catastrófico para la vida humana y las construcciones.

Al este, los gunas, que habitan el archipiélago de San Blas, ya están sintiendo los efectos del aumento del nivel del mar. Sus islas de belleza inigualable estarán entre las primeras en el mundo en extinguirse por el calentamiento global. Los países y Estados que han estimado los costos financieros de mitigar y responder al aumento del nivel del mar muestran que el precio será extremo, pero pocos están considerando los incalculables impactos culturales y sociales.

¡No piense que el lado pacífico del istmo será inmune a estos peligros! Solo pequeñas cantidades de aumento en el nivel del mar aumenta las posibilidades de inundaciones durante las mareas de tormenta. Tocumen, Costa del Este y otras tierras bajas serán muy propensas, más ahora que han perdido muchos manglares, que funcionaban como escudo protector.

Alternativas

Sin embargo, la ciencia nos informa de cambios que se pueden introducir para mitigar el calentamiento global. Panamá ya ha tenido un impacto increíblemente positivo en la reducción de las emisiones de CO2, ya que el canal evita que los barcos tengan que viajar por Sudamérica, lo que ha salvado la emisión de 700 millones de toneladas de dióxido de carbono a la atmósfera. No está mal para una pequeña franja de tierra y una zanja.

Pero no debemos ser complacientes. La Organización Marítima Internacional afirma que, sin intervención, las emisiones de carbono por actividades marítimas en el mundo podrían aumentar hasta 250% para 2050.

La industria del transporte marítimo cuenta con una gran cantidad de investigaciones para mejorar la eficiencia de los barcos, especialmente cuando un aumento en la eficiencia de combustión de solo un pequeño porcentaje puede resultar en ahorros financieros significativos que alcanzan los millones de dólares.

Los avances tecnológicos son una parte importante de la solución, especialmente en el diseño del casco, las nuevas fuentes de combustible y las mejoras del motor, pero igualmente importante es la introducción de mejores medidas operativas, como la adopción de “vapor lento” y la mejora de la logística a bordo y en los puertos, que puede tener impactos sorprendentemente grandes en la eficiencia y, por lo tanto, desempeñar un papel importante en la reducción de emisiones a nivel mundial.

Nuestras elecciones de estilo de vida también son importantes. Por ejemplo, la compra de productos cultivados localmente no solo ayuda a los agricultores locales, sino que también evita la necesidad de transportar productos refrigerados en barcos a alta velocidad; una de las formas de transporte más contaminantes.

América Latina y el Caribe dependen en gran medida del transporte marítimo, y es donde se realiza más del 90% de todos los movimientos internacionales de carga, una gran proporción de los cuales utiliza el Canal de Panamá.

Tenemos la responsabilidad de aprender del pasado para mejorar nuestro futuro. Hace millones de años, el pequeño istmo de Panamá jugó un papel increíble en la conducción de los cambios en el mundo. Aunque Panamá es pequeño, tiene la bendición de estar en una posición privilegiada para seguir ayudando a bajar las emisiones contaminantes y, una vez más, desempeñar un papel importante en un cambio positivo para nuestro planeta y para las poblaciones costeras, que serán las más afectadas por el aumento del nivel del mar.

Publicado por La Prensa: https://impresa.prensa.com/vivir/Panama-vez-oceano-nuevo_0_5192480746.html

My research question as a Smithsonian

My research question as a Smithsonian

Lauren Graniero, student at Texas A&M and STRI short term Fellow, just published another paper that helps us make sense of the significance of stable isotope ratios in skeletal material.

Lauren Graniero, student at Texas A&M and STRI short term Fellow, just published another paper that helps us make sense of the significance of stable isotope ratios in skeletal material.

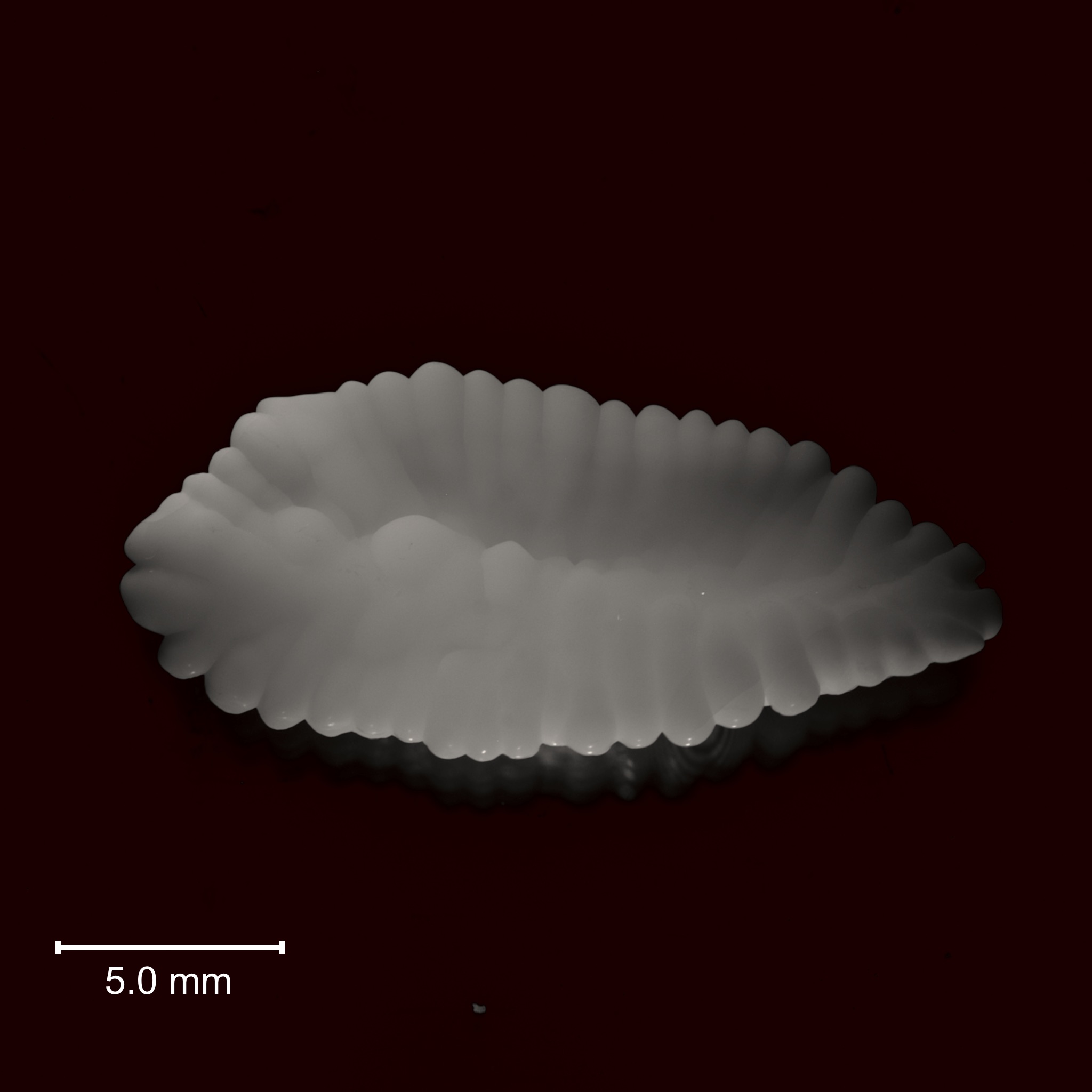

Caribbean coral reefs have transformed into algal-dominated habitats over recent decades, but the mechanisms of change are unresolved due to a lack of quantitative ecological data before large-scale human impacts. To understand the role of reduced herbivory in recent coral declines, we produce a high-resolution 3,000 year record of reef

Caribbean coral reefs have transformed into algal-dominated habitats over recent decades, but the mechanisms of change are unresolved due to a lack of quantitative ecological data before large-scale human impacts. To understand the role of reduced herbivory in recent coral declines, we produce a high-resolution 3,000 year record of reef

Follow the exploits of the O’Dea lab in the field on the

Follow the exploits of the O’Dea lab in the field on the

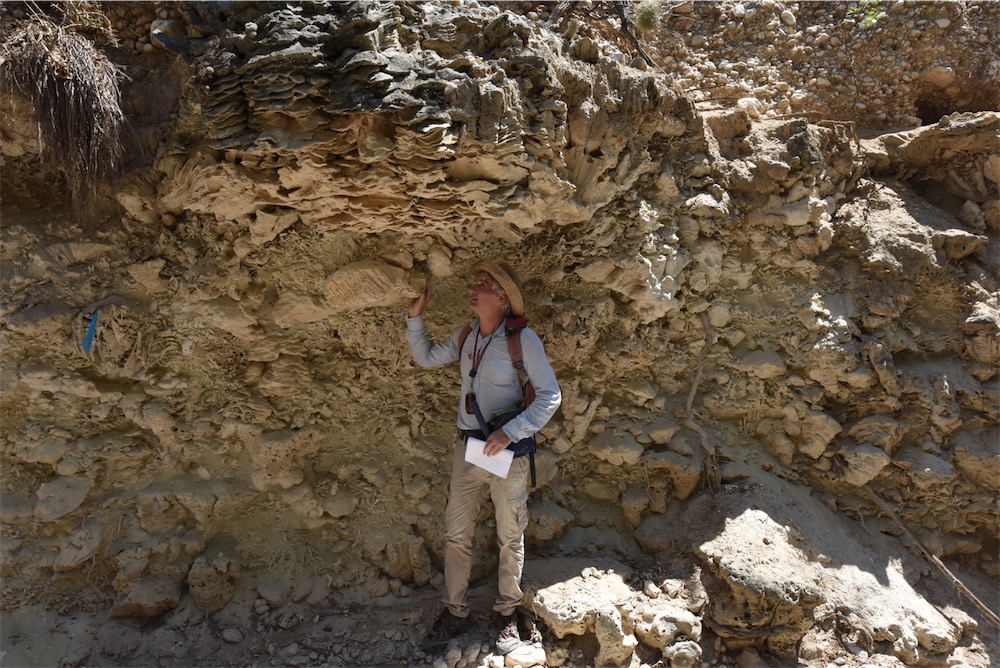

Three years ago Paul Taylor was inPanama scouting for Pleistocene bryozoans along the Burica Peninsula that juts out into the Pacific Ocean at the Panamanian and Costa Rican border. Neil MacGregor had just published the book “A History of the World in 100 objects” and I mentioned

Three years ago Paul Taylor was inPanama scouting for Pleistocene bryozoans along the Burica Peninsula that juts out into the Pacific Ocean at the Panamanian and Costa Rican border. Neil MacGregor had just published the book “A History of the World in 100 objects” and I mentioned

You must be logged in to post a comment.