Welcome!

The O’Dea lab is located at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama where we investigate tropical marine ecosystem dynamics across a variety of temporal and spatial scales to explore fundamental patterns of ecology and evolution in Earth’s most biodiverse environments.

Our research spans timescales from major geological events like the formation of the Isthmus of Panama to modern anthropogenic impacts such as overfishing and coral reef degradation. By integrating data across these temporal scales, we can better understand both natural ecosystem variation and human-driven change.

The aim of this historical approach is not only to reconstruct what the oceans were like in pre-human ‘pristine’ times, but to identify key drivers of ecological resilience and vulnerability in tropical marine systems.

Understanding these long-term dynamics is crucial for predicting and managing how these biodiverse, socially-valuable ecosystems will respond to future change.

Our work is supported by the Panama government (SENACYT), The US National Science Foundation, the National System of Investigators, the Smithsonian Institution, and donations.

We are normally to be found in the Surfside building in the Naos Island Marine Laboratories at the end of the Causeway, Amador, Panama City, República de Panamá (8.915250, -79.530944)

Email: odeaa@si.edu

Telephone: +507 212 8817

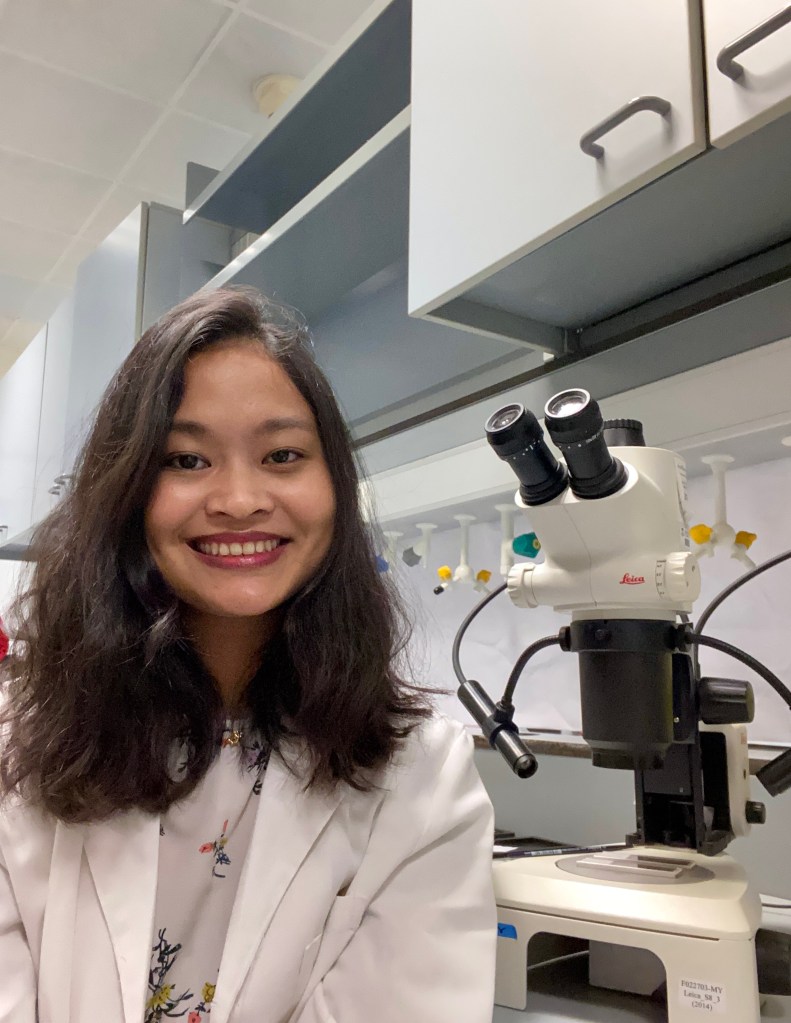

Look at some of our wonderful team:

You must be logged in to post a comment.